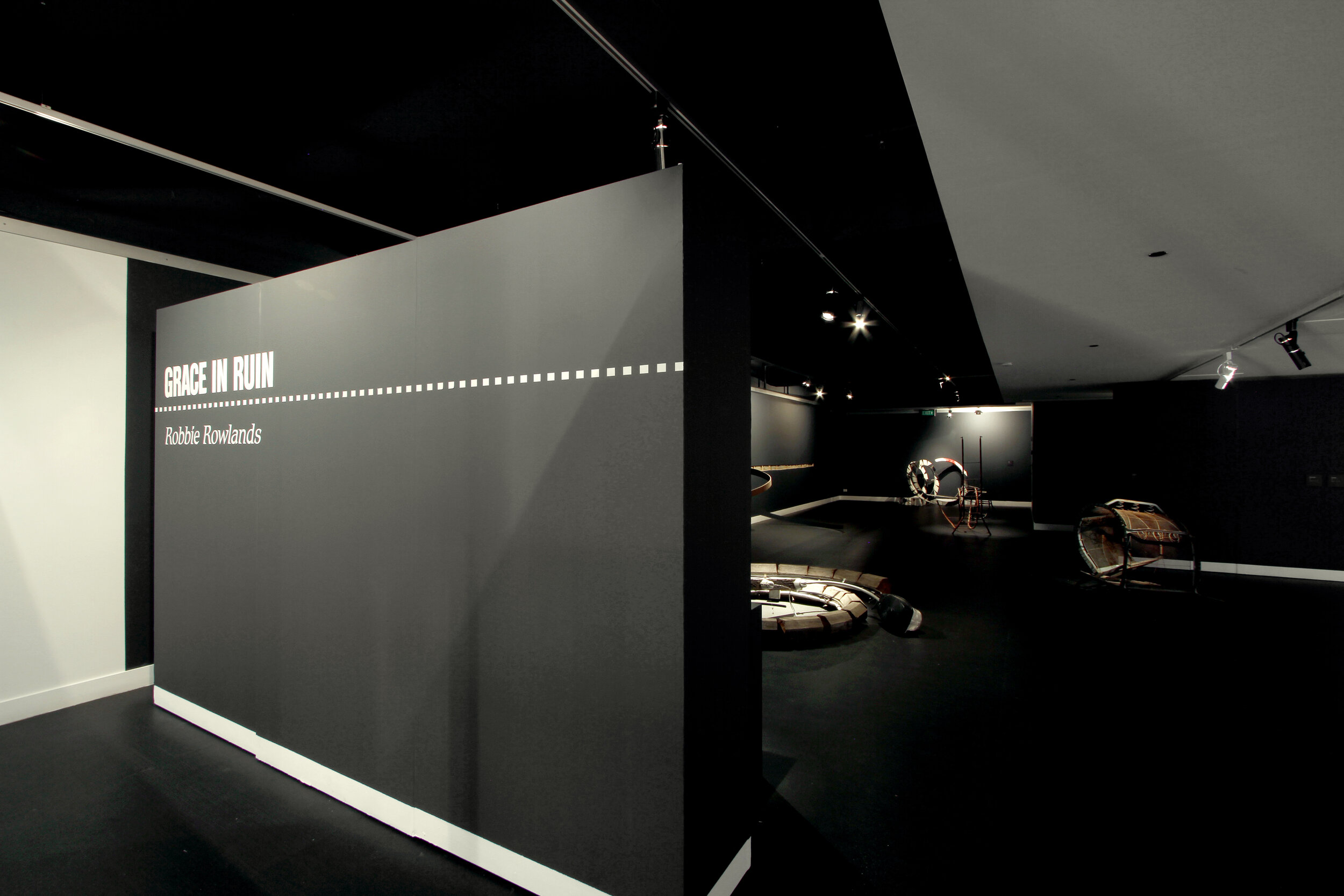

Grace in ruin

Gippsland Art Gallery

Sale, 2010

Essay Simon Gregg

Robbie Rowlands is a most unconventional sculptor. He cuts, bends and reshapes everyday objects of our world to facilitate encounters with another world entirely. His practice is formulated not by acts of creation, but by object modification and spatial renegotiation. We find the props that provide support to our lives have themselves become wilted and prone. Rowlands throws the finitude of the object into question, and engages the uncertainty of space and the ambiguity of time. In suggesting a break down of their composite orders, his artworks are able to modulate their concrete appearance, and usher in a transitional, temporal state. They play on the ambiguity of becoming, being and unbecoming; that is, their position on the scale between birth and death is a speculative matter.

Rowlands works with existing objects and spaces, which sometimes extends to entire buildings, in a practice that seeks to renegotiate the empirical, and challenge the way we see the world. His works apply transition and transformation to static objects and casts them as biological forms; prone and vulnerable, but also full of wonder and potential. For Rowlands, the process of decline and decay becomes an aesthetic event, and he manipulates the disintegrating form as a means of fathoming new forms – unique, bizarre and barely recognisable from their original shape. An ambiguity occurs that delininates functionality and aesthetics.

His process is one of simple cutting into objects, with repetition and with precision, with the result of that object becoming deformed. There is a necessary application of violence here, but it is perpetrated with a gentle respect for the form and its history; indeed, Rowlands’ transformations are often a means of examining the history of the object, while simultaneously accelerating its decline.

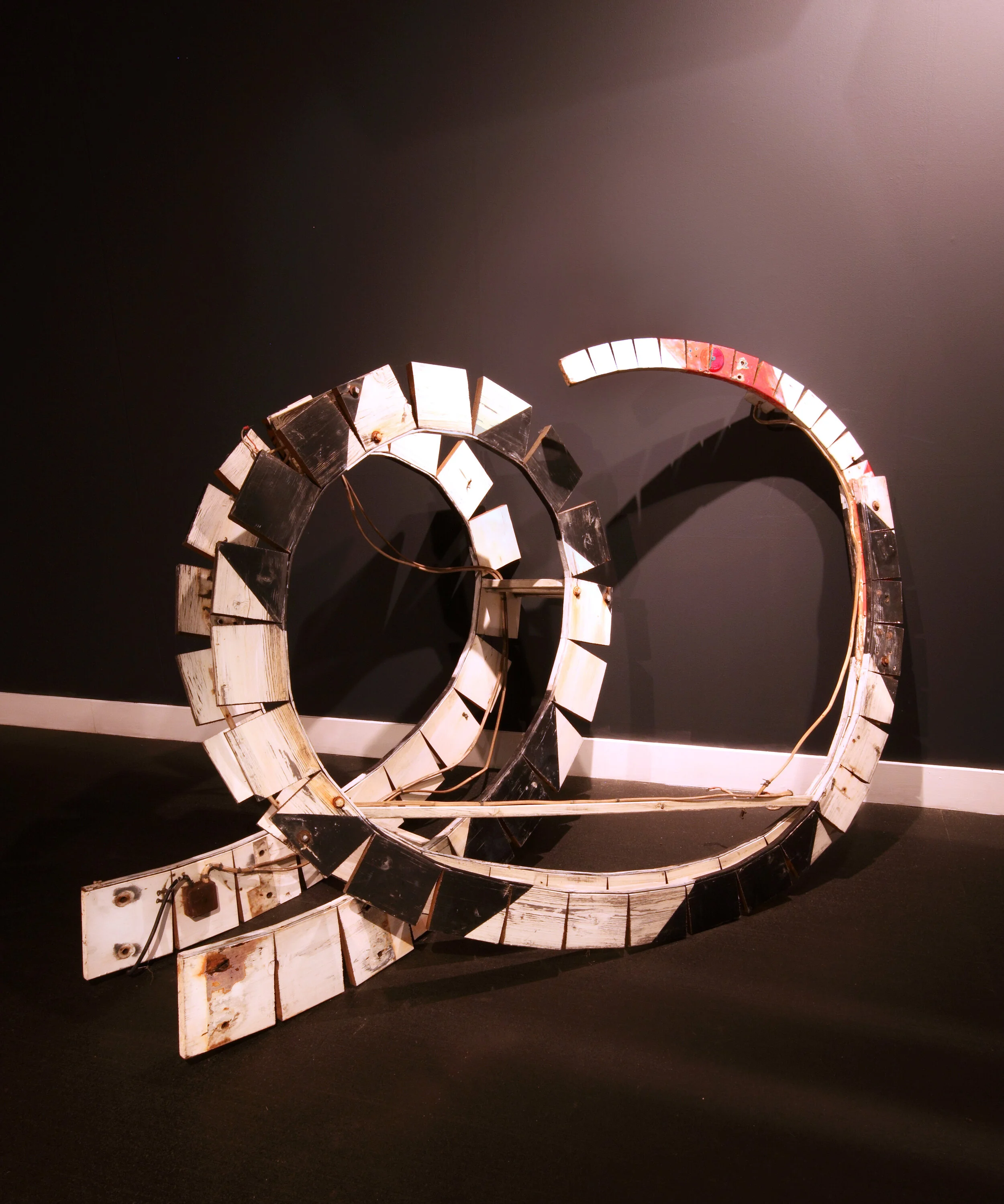

The path to dissolution brings about an uncanny modulation of any form. Once intact and purposeful, it now languishes in disuse. As decomposition sets in, surfaces rupture and inner structures collapse. The resulting rubble is often unidentifiable, before it disintegrates completely into dust and blows away. Rowlands’ works represent, in part, a synopsis of this process. He employs an exaggerated decay as an agent of awakening the inner beauty of objects. He shows that the carnage of time elicits a transformation that reveals the wonders within. The death of Rowlands’ objects is an act of transcendence, as they pass from one life (of purpose and utility) to the next (of aesthetic contemplation).

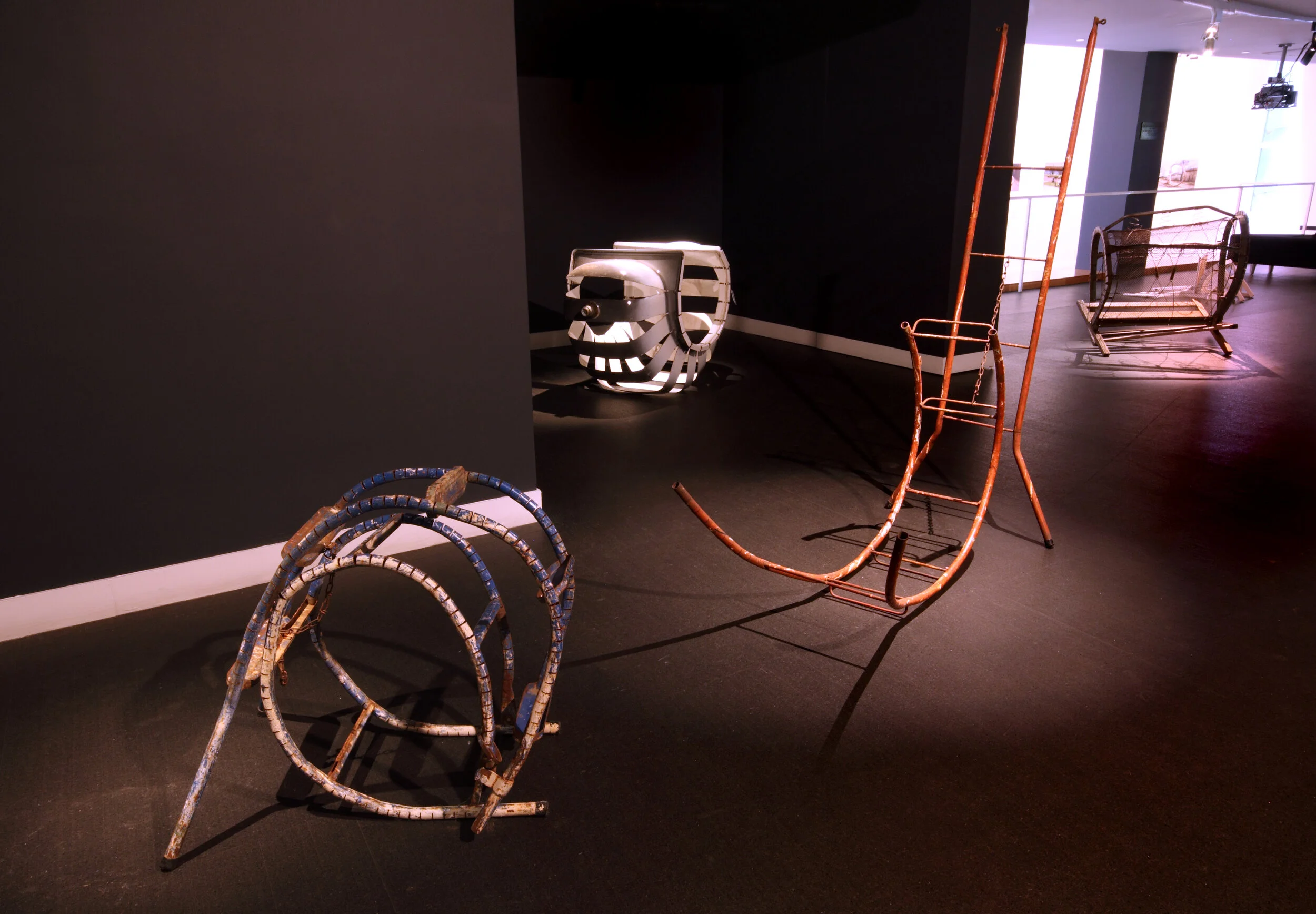

The nature of Rowlands’ donor objects bears some consideration here. He carefully selects objects that exist at the fringe of our awareness, being in such common use that we barely notice them at all. These might include bath tubs, chairs, tables and beds, through to entire houses. Within the built environment Rowlands exacts his program of radical decay upon street light poles, electricity poles, boom gates and football oval posts. This myriad of daily detritus, invisible while in use, ironically only become apparent to us through their newfound dysfunction. That the objects are presented to us as artworks implies a new meaning, and a new reading – stripped of all functionality the objects become aesthetic specimens.

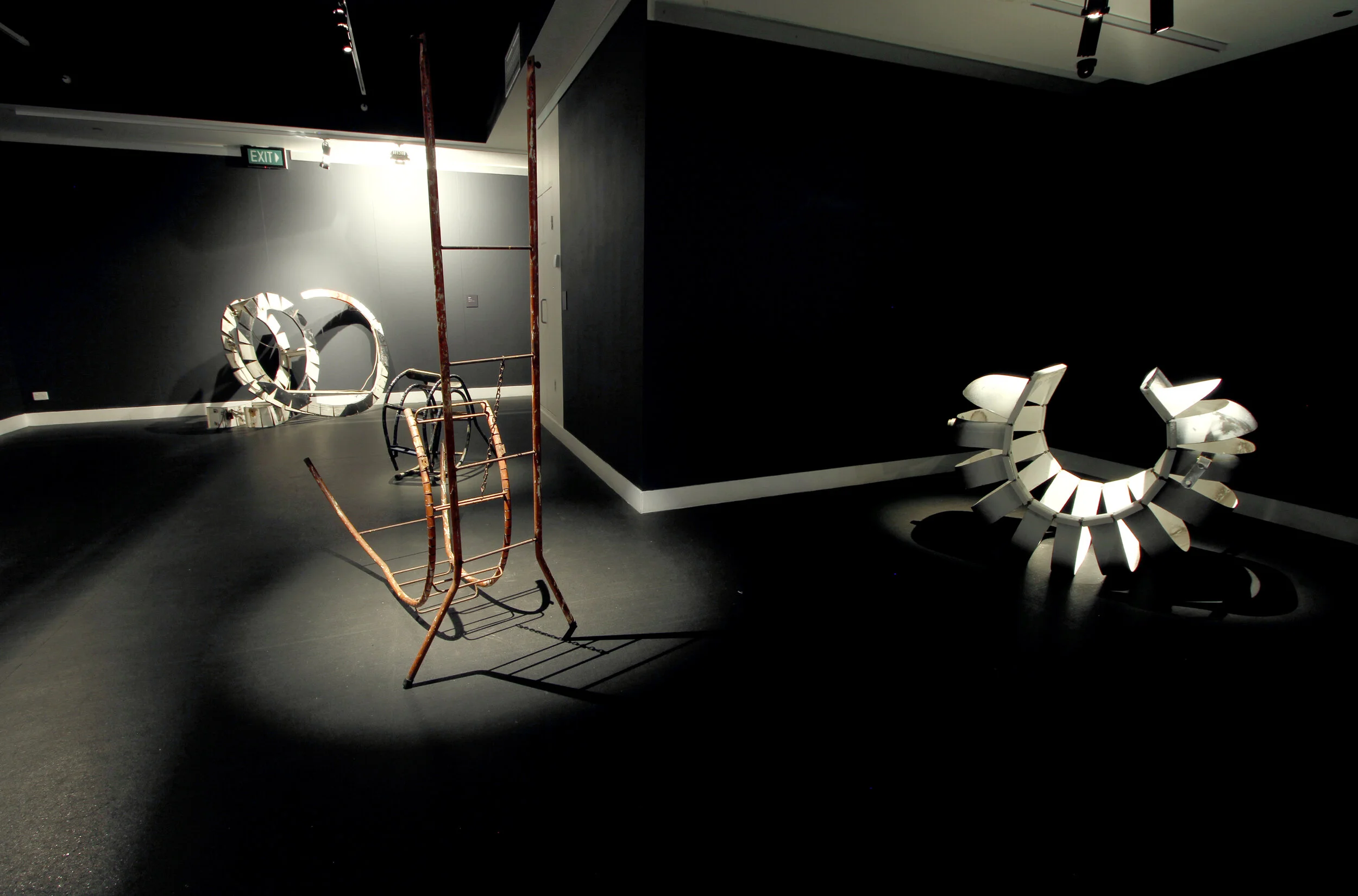

The act of cutting incisions into the objects has the effect of making them either curl outward or inwardly upon themselves. The simple timber chair becomes dissected and is splayed across the floor like the remnants of some bizarre medical autopsy. Ladders and crutches – both engineered for structural integrity – become wilted and themselves in need to support. Boom gates, beds and baths, meanwhile, curl inward in spirals that recall shell creatures. The recontextualisation of the object creates an altogether new form; a hybrid of a static man-made article and a still-evolving biological mutant.

Part of the attraction of Rowlands’ work is that we recognise something from our own world, which has been renegotiated to reveal qualities that had lain dormant. This subversion of the familiar achieves its greatest impact in Rowlands’ large scale interventions of buildings that have been scheduled for demolition. Here, Rowlands exerts a particular kind of deconstruction over built forms. His selective stripping of inside and outside surfaces – of peeling back the facade – might be better described as a kind of rebirth. These containers of space, be they industrial or domestic, pantheistic or secular, exude a fresh aroma of discovery once Rowlands has set his saws to work.

This careful structural dismemberment reveals buildings as fragile shells, and as we peer through the gaps he has created, we observe the rot and entropy of time. There is an undercurrent of scientific curiosity at play here, but the overriding achievement of Rowlands’ spatial work is that he transforms entire edifices into singular objects for consideration. Our reading of space is transformed, as we marvel at the way a single layer in a long unbroken strip has been dissected from the ceiling, walls and floor, and accumulated into an apple core-like spiral on the ground. The infliction of decay has never been more seductively imposed.

Project credits

Photography:

Christian Capurro (Gallery)

Wren (Studio)